Image copyright

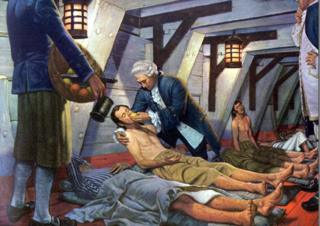

Institute of Naval Medicine

James Lind's experiment with citrus fruit was one of the first reported clinical trials in medicine

James Lind is remembered as the man who helped to conquer a killer disease. His reported experiment on board a naval ship in 1747 showed that oranges and lemons were a cure for scurvy. But why did the Royal Navy, which celebrates the tercentenary of Lind's birth on 4 October 2016, take nearly half a century to act on his findings?

For 18th Century sailors, disease during long sea voyages was often more dangerous than enemy action.

One British expedition to raid Spanish holdings in the Pacific Ocean in the 1740s lost 1,300 of an original complement of 2,000 men to illness.

The commander, George Anson, said "almost the whole crew" was afflicted by symptoms including a "luxuriancy of funguous flesh… putrid gums and… the most dreadful terrors".

Many sailors suffered "a strange dejection of the spirits" and lay immobile, while others who "resolved to get out of their hammocks, have died before they could well reach the deck".

Image copyright

Admiralty Library, Naval Historic Branch

Scurvy was reported to cause "funguous flesh… putrid gums and… dreadful terrors"

Frequent outbreaks of disease tormented crews and various cures were championed.

The explorer Captain Cook recommended malt and sauerkraut, while others swore by "elixir of vitriol" (a dilute solution of sulphuric acid), blood-letting and applying a piece of turf to the patient's mouth to counter the "bad qualities of the sea-air".

Among the array of imaginative remedies were some that proved effective.

Sailors who ate the ship's rats were inadvertently protecting themselves – as the animal synthesizes its own vitamin C.

Citrus fruit – another source of vitamin C – had already been suggested as a cure by some.

The explorer Sir Richard Hawkins recorded in 1622 that "sower lemons and oranges" were "most fruitful… I wish that some learned man would write of it".

More than a century later, a learned man fulfilled that wish, with a text which earned him a place in scientific history.

Image copyright

John Hepner

James Lind is described by the Royal Navy as "the father of naval medicine"

James Lind was the son of an Edinburgh merchant and became a medical apprentice in the city before joining the Royal Navy as a surgeon's mate in the late 1730s.

His service allowed him to observe the effects of scurvy at first hand.

In 1747, on board HMS Salisbury, he carried out one of the first controlled clinical trials recorded in medical science.

He took 12 men suffering from similar symptoms of scurvy, divided them into six pairs and treated them with remedies suggested by previous writers:

- a quart of cider a day

- 25 drops of elixir of vitriol, three times a day

- half a pint of sea-water a day

- a nutmeg-sized paste of garlic, mustard seed, horse-radish, balsam of Peru, and gum myrrh three times a day

- two spoonfuls of vinegar, three times a day

- two oranges and one lemon a day

By the end of the week, those on citrus fruits were well enough to nurse the others.

Image copyright

other

Lind's "Treatise of the Scurvy" described his experiment on board HMS Salisbury

Dr Lind's "Treatise of the Scurvy", containing a celebrated review of literature on the disease, appeared in 1753, by which time he was a practising physician in Edinburgh.

He prided himself that he had conquered a condition which "during the last war, proved a more destructive enemy, and cut off more valuable lives, than the united efforts of the French and Spanish arms".

But it was not until 42 years later that the Admiralty first issued an order for the distribution of lemon juice to sailors. Historians still debate why it did not act upon Dr Lind's discovery earlier.

What is scurvy?

- A condition caused by a lack of vitamin C.

- Most animals can manufacture their own vitamin C in their bodies – exceptions include humans, monkeys and guinea pigs

- A lack of vitamin C means that collagen, a protein found in body tissue such as skin, cannot be replaced, leading to tissue breakdown

- A diet with no vitamin C could lead to symptoms within four weeks

- Adult patients may suffer from fatigue, bleeding gums, joint pain, shortness of breath, slow-healing wounds and potentially-fatal heart problems

- Guava, chillies and red peppers contain much more vitamin C than citrus fruit

(Source: British Dietetic Association)

Jane Wickenden, from the Institute of Naval Medicine, said she believed it was partly because Dr Lind's treatise drew no clear conclusions.

She said: "The account of the experiment only takes up four pages. The remaining 450 pages deal with other treatments including fresh air and exercise."

Adding to the confusion were rival cures, including the malt and "Sour Kroutt" favoured by Captain Cook.

Ms Wickenden added: "Captain Cook was the self-publicist that Lind wasn't. He had travelled around the world and had the ear of the Admiralty."

But the treatise was widely circulated. Following publication of the first edition, Dr Lind was appointed to the position of Chief Physician to the Royal Hospital at Haslar in Hampshire.

Further editions followed as well as French and German translations.

In 1795, the year after Dr Lind's death, the Admiralty finally took advice from its own medical staff and made the issue of lemon juice compulsory on ships.

Image copyright

other

Lind is honoured by the Institute of Naval Medicine, with a lemon tree occupying its official crest

Yet, despite the Navy's efforts, outbreaks of scurvy continued to affect seafarers.

Ms Wickenden said: "They didn't appreciate that the power of lemons to counteract scurvy deteriorated with storage and also with some of the preservation methods used, like boiling the juice, which destroys the vitamin C."

Dr Lind's suggestion that the power of lemons lay in their acidity led the Admiralty to try cheaper limes from a new British plantation in the Caribbean in the 1860s.

The fruit, containing about half the vitamin C content of lemons, was less effective in preventing scurvy among British sailors, or 'Limeys' as they became known.

Not until vitamin C was identified in 1928 was the disease effectively conquered at source.

However, in the Royal Navy, Dr Lind is remembered as a hero.

Ms Wickenden said: "Lind conducted what is largely regarded as the first clinical trial and is seen as the father of naval medicine."

A lemon tree now adorns the official crest of the Institute of Naval Medicine, which is based near the former Royal Hospital Haslar where he worked.

Leave a reply

Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/httpdxfc/say-med.com/wp-includes/class-wp-comment-query.php on line 405